Once you understand what readability statistics mean, you really can improve your writing.

Are you using Editor?

If you haven’t started using Editor within Word or Outlook to improve your writing, check out my review of Editor. It’s also a guide to getting the most from each function within Editor.

As promised in that article, now it’s time to look at the one Editor function I didn’t cover: the readability statistics. Hidden behind Editor’s ‘Document Stats’ button, these statistics will be familiar if you have used them as part of the spellcheck tool within older versions of Word.

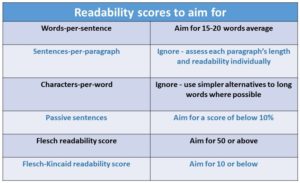

Now I’ll go through each of the readability statistics within ‘Document Stats’ one-by-one, but here’s a quick summary to set the scene:

Words-per-sentence

As a rough guide, for most marketing and business writing, your average words per sentence number should be no more than 20, and ideally lower. I’m usually happy if my writing is around the 17 mark.

When you write with 20+ words per sentence, you run the risk of:

– Getting clumsy or complex with your grammar.

– Making it hard for readers to digest each of the points you’re making.

There are times when writing with an average above 20 is still very readable, such as a technical piece aimed at a very knowledgeable readership. But all the research I’ve seen points to an average sentence length of 15-20 words being the sweet spot.

However, consider the medium you’re writing for. Really short sentences averaging below ten words may be perfect for adverts or Tweets, but could look ‘bitty’ in a lengthy thought leadership piece.

Richard’s readability tip:

You can boost readability by varying sentence length.

Mixing short and long sentences can keep readers interested.

Sentences-per-paragraph

Opinion online varies greatly about what’s a ‘good’ average for sentences-per-paragraph. Here are examples of the guidance you’ll find:

– “In general, paragraphs should have 5-8 sentences.”

– “Commercial writers like to keep their paragraph length between three to four sentences.”

– “When it comes to maintaining a reader’s attention, a good rule of thumb might be to avoid writing more than five or six sentences in a paragraph before finding a logical place to break.”

– “There are 3 to 8 sentences in a paragraph.”

As you can see, there are lots of opinions! My take on it is that the sentences-per-paragraph metric is worth looking at, but it’s not a particularly useful score. Let me tell you why…

You could have a low average of around two sentences-per-paragraph. But your writing could include easy-to-read one-sentence paragraphs mixed with several dense, complex paragraphs of five sentences or more.

The average in a case like that is really of no use at all. It doesn’t tell you anything about the readability of your writing. The overly-long, complex paragraphs would cancel out the short ones.

Look at each paragraph individually

Instead, I’d recommend this method to improve readability when it comes to paragraphs:

Step 1: Look at each paragraph of more than three sentences, or more than 40 words, and assess them for clarity and readability.

Step 2. In most cases, you may find that a paragraph of that length would be more readable if you split it into two, perhaps with a little editing to make that work.

Step 3. If you decide to keep the paragraph at its current number of sentences, make sure it’s especially readable…

How to write more readable paragraphs

Here are some tips for improving any paragraphs you identify as troublesome, or for writing better paragraphs in the first place:

– Cover one main point or theme per paragraph.

– The first sentence should ideally make the reader want to read the next.

– Each sentence in a paragraph should flow into the next sentence, and from the sentence before it.

– Break a paragraph as soon as the reader might find it too long or too complicated.

– If you’re including lots of technical words in a piece for a non-technical readership (for example, names of health conditions and medications in a wellbeing blog), break paragraphs even more often than usual.

– Vary paragraph length: there’s nothing wrong with some one-sentence paragraphs.

– Avoid too many numbers in a single paragraph. If every sentence in a three-sentence paragraph contains numbers, percentages or statistics, if can look especially complex and overwhelming.

There is lots more to say on the art of writing clear and readable paragraphs, but hopefully these tips will help. In particular, please don’t see the sentences-per-paragraph average as especially relevant – work on addressing potentially problematic paragraphs individually instead.

Characters-per-word

Experts seem to agree that something in the region of 4-5 characters (letters) per word is probably where your writing will be. But I don’t pay much attention to this metric.

That’s because most of your writing will be full of short words such as and, or, it, is, you, our, are, from, for… and so on. You’d have to be writing very technical content with lots of very long words before your characters-per-word average gets much higher than 5.

As an example, even something as technical as the 10,000 word article ‘Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) as an anti-aging health product – Promises and safety concerns’ scores only 5.6 characters-per-word.

So my advice would be to ignore this score. If the other readability scores within Document Stats are OK, you don’t need to worry about characters per word.

However… do take a few minutes to read through your writing and look out for any long words. Use simpler alternatives where possible, but don’t obsess over characters-per-word if the other stats look good, and if your gut feel is that your readability is OK.

Richard’s readability tip:

Use Thesaurus.com to help you find simpler alternatives to long words: but if a long word really is the only one that conveys the right meaning, stick with it!

Passive sentences

The ‘Document Stats’ box tells you what percentage of your sentences are passive. But before looking at the score you should aim for, what is a passive sentence anyway?

– In a passive sentence, something is BEING DONE to something or someone.

– Contrast this with an active sentence, where someone is DOING something to something or someone.

Here are two examples:

Passive: The fly was swatted by the man.

Active: The man swatted the fly.

Passive: The moon was orbited by the spacecraft.

Active: The spacecraft orbited the moon.

An active sentence is usually shorter, clearer and easier to read than the passive alternative.

Let’s look at another example with longer sentences to illustrate this more clearly. Here, sentences 2 and 3 in the paragraph are passive in the first version and active in the second:

Passive: ACME secured its first contract to deliver dynamite to Roadrunner in 1949. Since then, more than 1,000 units have been deployed nationally. In 1952, ACME was selected as the technology provider for Wile E. Coyote destruction programme.

Active: ACME secured its first contract to deliver dynamite to Roadrunner in 1949. Since then, the company has deployed more than 1,000 units nationally. In 1952, the Wile E. Coyote destruction programme selected ACME as its technology provider.

The difference is subtle perhaps, but if you use active rather than passive often across a long piece of writing, it creates a better experience for the reader.

Warning: passive sentences are sometimes OK!

Look at this final example:

Passive: You can choose for your salary to be paid weekly or monthly.

Active: You can choose for your employer to pay your salary weekly or monthly.

Here, the passive version is shorter than the active version, and maybe slightly easier to read. You need to use your judgement and common sense rather than simply eradicate all passive sentences from your writing.

What’s a good score for passive sentences?

In terms of using the readability statistics within Editor:

– If your score is below 10%, you’re probably doing OK and can move on.

– If your score is above 10%, identify the passive sentences and turn some into active where you can, and where it genuinely improves readability.

Learning to use the active voice rather than passive is a way that most people can improve the readability of their writing.

And how do you identify the passive sentences?

You can do it within the Editor tool. Click ‘Clarity’ in the ‘Refinements’ section and look at each issue that Editor identifies.

When you see ‘Saying who or what did the action would be clearer’ it’s Editor’s way of identifying the passive voice. Sometimes, Editor will also suggest an active version of the sentence.

An even better way to identify your use of the passive voice is to use a specialist online tool. Try the excellent and free passive voice detector at Datayze. The free Hemingway Editor also identifies passive sentences, as does the grammar check within the paid-for Grammarly service.

Richard’s readability tip:

Hemingway Editor does more than check for passive sentences.

It’s a superb tool that identifies where you may need to keep editing to improve readability.

Flesch and Flesch-Kincaid readability scores

These are two examples of several readability statistics known as ‘fog indexes’. Some were originally developed to help teachers, librarians and publishers make decisions about the purchase and sale of books, and especially children’s books. Others were developed to assess the readability of technical manuals or general business writing.

Although they weren’t designed as measures of readability for marketing copy and content in the 21st Century – they CAN help you improve your writing skills.

Flesch reading ease

This assesses sentence length and the average number of syllables per word. Longer sentences and more syllables per word both mean writing is generally harder to read.

Scores range from zero to 100. The higher the score the better, as it means more people can readily understand the piece of writing.

Standard writing averages 60 to 70 and this is where your marketing writing should probably be.

However, often perfectly good writing will score less than this. So I’d suggest 50 as the minimum score to aim for – but aspire to get up to 60 or above if you can. As always, use your judgement and common sense to guide you.

Consider the type of document and the likely readership profile too. Reaching a score of 70 may be almost impossible for a technical piece for a very well-educated audience. A score of 50 may be too low for a piece of consumer content aimed at a broad readership.

Flesch-Kincaid grade level

This also checks readability based on the average number of syllables per word and the average number of words per sentence.

It indicates the number of years’ schooling required before someone can easily read the text. The lower the score, the more readable your writing. But don’t think that a low score means you are insulting your readers’ intelligence.

Standard writing for adults approximately equates to 7-8 years’ schooling. That’s because our reading ability improves very little after our eighth year of schooling.

If you score 7-8 with this index that’s very good. In my experience, anything below 10 is probably OK. If you score 11-12 or higher, see if you can edit accordingly. But again, use your judgment and common sense too.

Look at these scores as valuable readability statistics and do some editing if your writing falls outside of the guidelines I’ve covered above. Focus on any long sentences to see if you can break them into shorter sentences. Consider also if you are consistently using long words where shorter alternatives would be just as good.

Summary: learn to love readability statistics

Readability statistics can do much more than help you improve individual pieces of copy or content. Using them can actually help you learn to be a better writer. They focus your attention on areas where you may need to improve, potentially leading to long-term improvements in your ability as a writer.

SIGN UP FOR MARKETING BOOSTER

Would you like to get my Marketing Booster blogs straight into your inbox? Tips, techniques and inspiration for better written communications.